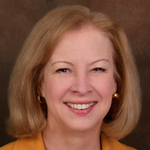

The President's Corner

A Path to Joy

Growing up with three brothers on a Minnesota farm, I learned to read early, and voraciously. I hid books all around the farm—in the hay mow, the laundry hamper, the pantry, the garden shed. My parents didn't object to my reading, but they did object to my reading instead of doing my chores. I was an omnivorous reader—I would read ANYTHING. Having early exhausted the limited offerings of the Nobles County Bookmobile, I checked books out of the public library when we got to Worthington (population 9,500), about every other week. The library allowed me to check out just five books at a time, so I didn't bother looking for specific titles. I checked books out by SIZE. I walked up and down the stacks looking for the thickest books. The bigger the book, the better. I never read any of the traditional children's or young adult books—they were too small to meet my size criterion.

As an early teen, I read a lot of Michener's Hawaii (937 pages), Dickens' David Copperfield (974 pages), George Elliot's Middlemarch (904 pages), Tolstoy's War and Peace (1392 pages), Thackeray's Vanity Fair (867 pages), Darwin's Origin of Species (706 pages), Mitchell's Gone With the Wind (1037 pages), Cervantes' Don Quixote (972 pages), heavy collections of Shakespeare's plays, and many other lengthy volumes.

Such copious and eclectic reading helped me develop a large vocabulary, but I didn't always understand what the words really meant. I was exposed to other lives and times even if I didn't fully comprehend the experiences (let's just say that reading Hawaii at 13 was an eye opener). My extensive reading resulted in my ability to analyze and understand human behavior, to organize ideas, and to express myself in writing, although I didn't recognize the value of those skills at the time.

I attended Fulda High School (Fulda, population 1,100), back in the olden days before MS Magazine and Gloria Steinem, back when the Equal Opportunity Act had just been passed forbidding discrimination on the basis of race and sex in employment (the Act, by the way, almost didn't include the category of SEX). My school counselor, who was also the physics teacher, was of a generation before equal opportunity. He said I was suited to go to college to be a high school English teacher, a job I could do until I got married, or go to vocational school to become a secretary so that I would have a career to fall back on.

At Augustana College, I had no idea what I would do with my education, but I knew two things: I wanted to read and study everything, and I would not become a high school English teacher or a secretary. In fact, I was determined that I would not be a teacher of any kind because, although I had not formed any clear sense of female empowerment, I was stubborn and, as many young people do, I resisted the direction into which I was being pushed.

I graduated from Augustana with a comprehensive English literature major, minors in French and Spanish, and no job. Early plans to become a translator for the U.N. diminished when I discovered I had no talent for other languages. Both my Spanish and French teachers were Cuban, and a French-speaking friend told me once that I had the French accent of a Spanish mule-team driver. My advisor at Augie urged me to go to graduate school. Instead I moved back to Minnesota to help my brother start a pair of behavioral therapy group homes for teenagers. I handled publicity, public relations, written materials—anything to do with writing and public speaking. As the group homes took off, I was invited to address students in psychology classes at Mankato State College, local philanthropic groups, advisory boards, and the National Association of Behavioral Therapists. And I taught the staff at the group homes to write reports and assessments. I loved it!

Long story coming to an end: three years later, I went back to school (University of Arizona and University of Wisconsin) with the express intent of teaching English in college. I love teaching! From the first moment I stood in front of a class full of students, I was at home. Every day for over three decades at the University of Wisconsin-Eau Claire, I have counted myself extraordinarily fortunate to have a career which brings me joy. I am not saying that everything about teaching is peachy (I disliked academic politics and grading freshman composition papers, for example). I am not saying that everyone should become a teacher. What I am saying is that if I could, I would give all students the gift of a career that brings them joy.

The path to a career that you love is not necessarily direct—mine certainly wasn't—but we can look at what we choose to do, in my case reading and writing, and recognize what we love to do and what we are good at. Find a way to turn that into your career. Some of you were fortunate enough to attend the workshops led by Susan de la Vergne at the 2013 Sigma Tau Delta Convention in Portland. She shows liberal arts graduates, especially English majors, how to turn what they are good at into business careers (see especially de la Vergne's publications for English majors).

In a 2005 commencement address, the late Steve Jobs said, "Your time is limited, so don't waste it living someone else's life. Don't be trapped by dogma—which is living with the results of other people's thinking. Don't let the noise of others' opinions drown out your own inner voice. And most important, have the courage to follow your heart and intuition. They somehow already know what you truly want to become. Everything else is secondary."

Don't be discouraged if you have to take on other kinds of work on your way. As an adult, I have worked as a bartender, waitress, bookkeeper, typist, grocery store sample person, telemarketer, encyclopedia sales person, motel reservationist, and paralegal (for just one day). All of those were steps on my way to learning what I love to do: read, write, and help others to do the same. Now I am giving back and enjoying myself at the same time as the President of the Board of Directors of Sigma Tau Delta.